Independent Learners, Math

In THIS article, “The Faulty Logic of The Math Wars” in the New York Times, Alice Crary, a philosophy professor, and W. Stephen Wilson, a math professor argue that the ideals that math reformists claim to be working towards when removing standard algorithms (such as long division) from elementary math textbooks are actually being moved away from if the thought processes behind the algorithms are analyzed differently.

Today the emphasis of most math instruction is on — to use the new lingo — numerical reasoning. This is in contrast with a more traditional focus on understanding and mastery of the most efficient mathematical algorithms. …

The reformist’s case rests on an understanding of the capacities valued by mathematicians as merely mechanical skills that require no true thought. The idea is that when we apply standard algorithms we are exploiting ‘inner mechanisms’ that enable us to simply churn out correct results. We are thus at bottom doing nothing more than serving as sorts of “human calculators.” …

This mechanical image of calculation is the target of a number of philosophical critiques. … Wittgenstein suggests that analogies between mathematical computations and mechanical processes only seem appealing if we overlook the fact that real machines have parts that bend and melt and are invariably subject to breakdown. … That is, it seems clear that, in order to be justified in believing that I have mastered an algorithm, I require a type of mental activity that isn’t simply causally generated. Far from being genuinely mechanical, such calculations involve a distinctive kind of thought.

That the use of standard algorithms isn’t merely mechanical is not by itself a reason to teach them. It is important to teach them because, as we already noted, they are also the most elegant and powerful methods for specific operations. This means that they are our best representations of connections among mathematical concepts. Math instruction that does not teach both that these algorithms work and why they do is denying students insight into the very discipline it is supposed to be about.

While reformists claim the need to change traditional math is based on the need to promote independent thought, the authors draw parallels to other subjects which are not being argued (usually) to start requiring creative thought in the early grades.

To begin with, it is true that algorithm-based math is not creative reasoning. Yet the same is true of many disciplines that have good claims to be taught in our schools. Children need to master bodies of fact, and not merely reason independently, in, for instance, biology and history. Does it follow that in offering these subjects schools are stunting their students’ growth and preventing them from thinking for themselves?

Further, the reasoning the reformists so desire needs to be built upon a solid foundation of “bodies of fact” such as parts of cell, the dates of wars fought in America, and the basic algorithms of math. If you do not know the basics, it will be difficult for someone to think deeply about more difficult topics within a subject. No one is arguing that the why should not be taught; let’s just not do a disservice to our students by not showing them the best way to do something. In Gideon we always aim to teach the why AND the best. In higher addition for example, visual movement exercises among place value (such as changing 12 ones into 1 ten and 2 ones) are used before carrying or regrouping, but the basic algorithm of putting a 1 above the tens column to aid in speedy addition is practiced until mastered.

Even if we sympathize with progressivists in wanting schools to foster independence of mind, we shouldn’t assume that it is obvious how best to do this. Original thought ranges over many different domains, and it imposes divergent demands as it does so. Just as there is good reason to believe that in biology and history such thought requires significant factual knowledge, there is good reason to believe that in mathematics it requires understanding of and facility with the standard algorithms.

Read the entire article HERE.

This article received a lot of comments such as these below:

John, an outraged mathematician from NY remarked:

How would the reform template work if applied to learning a musical instrument? What would the result be if beginning guitar students were not taught the basic chords? A lot of wasted time and a cacophony. Creativity can and should come later, once the basics are mastered. The same is true in mathematics.

(Another) John, a college professor from VA said:

I am … a multilevel modeler — aka, fancy statistics. … it would have been impossible for me achieve what I have without their instruction in what I am now being told was a method that limited my creativity.

The ability to perform basic arithmetic operations without thinking too much about them frees me … to think more about more complex mathematical operations/concepts.

Occasionally, I have students who have difficulty with simple arithmetic operations. These students also have difficulty understanding how to set up the models that they need to analyze their data and perhaps more importantly, they have difficulty interpreting the results.

Basic arithmetic operations are the simple sentences of mathematics and by extension, of disciplines such as statistics that rely on arithmetic operations. If you do not know how to construct a simple sentence, paragraphs would seem to be out of reach.

Read the rest of the comments HERE by scrolling the bottom of the page.

For more thoughts on this article and subject go HERE to Joanne Jacob’s blog where she links up with articles from Barry Garelick who discusses that reformists claim to be teaching the superior ‘understanding’ instead of a traditionalist’s mere ‘skills’:

. . . The reform approach to “understanding” is teaching small children never to trust the math, unless you can visualize why it works. If you can’t “visualize” it, you can’t explain it. And if you can’t explain it, then you don’t “understand” it.

Independent Learners, Young Learners

This is a heart warming article from washingtonpost.com about how one girl is so grateful for her father’s involvement and interest in her education as it really made a difference.

Here’s a sweet Fathers Day piece by Santa Clara University student Nicole Pal about how her father, Allan Pal, influenced her education. She grew up in San Jose, California, and will graduate in 2014 with a degree in web design and computer engineering. This summer she is building a solar-powered home “Radiant House” for the Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon competition.

Here are some key points I pulled from the article and advise our Gideon parents to do.

Believe in your children! Even when they struggle, be patient and assume they can overcome it.

The most precious gifts I received as a child were a white board and a book about bridges. I never questioned whether I could succeed as an engineer, and as I head into my final year of engineering school at Santa Clara University, I realize my dad played a huge role.

While some young girls might give up on a math question if they didn’t know the answer, my father was patient enough to walk through a problem with me- not just walk me through it. He let me re-work problems until the dry-erase marker was whittled to a stub. I was never tempted to smile, nod and simply pretend I understood. I always keep the whiteboard in mind when tutoring younger girls in algebra.

I can still remember something my father said to me once after graduating college. We had a new employee still in high school who was very self assured and capable. He said, “She reminds me of you. She can do anything she wants.” While I knew my parents thought I was smart and wouldn’t allow me to give up during difficult projects when I felt like quitting, this statement has stayed with me and given me confidence on days I needed it. Parents, your words have a impact. Make them inspiring!

Involve them in the household repairs, projects, and everyday calculations like cooking.

My father, who is an engineer with a microprocessing company, encouraged me to be hands on in whatever project he was working on. I remember learning how to use a saw and gleefully shouting “timber” as 2x4s hit the floor. … I’m passionate about engineering now because it helps me make sense of the world. By letting me problem-solve and get hands on with projects as a young child, I’ve learned how to make the world compute.

This helps the child see the real world application of all the things he is learning. It’s one thing to do a word problem about a recipe and another to cook it correctly yourself.

Develop a strong work ethic within their character.

One of the biggest ways my father nurtured my advancement in engineering was helping me find my passion and encouraging me to put in the hard work.

A strong work ethic will carry them through the times when things aren’t easy and fun. While doing another supplemental math program, I would whine and complain that none of my friends had to do this. I would try any way possible to get out of doing it most days. He would simply ignore my frustration and tell me to try again.

Even while doing their dream job, there will be times they have to do tasks or deal with problems they would rather not. Learning to deal with hard work early helps them keep going later in life. Grit can make a big difference in the path to success.

Read the entire article HERE.

Independent Learners, Reading, Young Learners

Summer is here! Camp! Swimming! All day play!

Reading!

Wait, what?

Yes, reading! Think of all the time now your child has to get lost in a book. This is a great way to avoid the summer slide of losing some of the great comprehension skills gained during school year. Your child can read about new places and fun experiences while gaining vocabulary and background knowledge that will aid in the fall. Encourage children to read a wide variety of topics and types of materials – books to magazines to comics to newsletters. Allow your children to pick out titles based on their interests to keep summer reading fun and enjoyable. You could read the book along with your child to create discussions. Read parts of it aloud to one another, especially an adventure or mystery, and get creative with the voices of characters.

This article from the Idaho Statesmen has other great ideas to make reading fun especially for younger children.

Read them a story, Richards says. That sounds simple enough, but there are nuances to making it a lasting experience.

– Be familiar with the text — even if you just give it a quick scan before you start reading.

– Work on varying your voice so you don’t deliver it in a monotone.

– Make it a shared experience. Hold the book close to the child so they can see the pictures and the words. Let them touch it.

For older students, encourage them to go beyond the latest book that is being turned into a movie. Have them take a look at classical literature, historical fiction, and biographies to keep pushing their comprehension and preparing for college level materials. According to this

article from KERA,

“…after the late part of middle school, students generally don’t continue to increase the difficulty levels of the books they read.”

Last year, almost all of the top 40 books read in grades nine through 12 were well below grade level. The most popular books, the three books in The Hunger Games series, were assessed to be at the fifth-grade level.

Last year, for the first time, Renaissance did a separate study to find out what books were being assigned to high school students. “The complexity of texts students are being assigned to read,” Stickney says, “has declined by about three grade levels over the past 100 years. A century ago, students were being assigned books with the complexity of around the ninth- or 10th-grade level. But in 2012, the average was around the sixth-grade level.”

Most of the assigned books are novels, like To Kill a Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men or Animal Farm. Students even read recent works like The Help and The Notebook. But in 1989, high school students were being assigned works by Sophocles, Shakespeare, Dickens, George Bernard Shaw, Emily Bronte and Edith Wharton.

Now, with the exception of Shakespeare, most classics have dropped off the list.

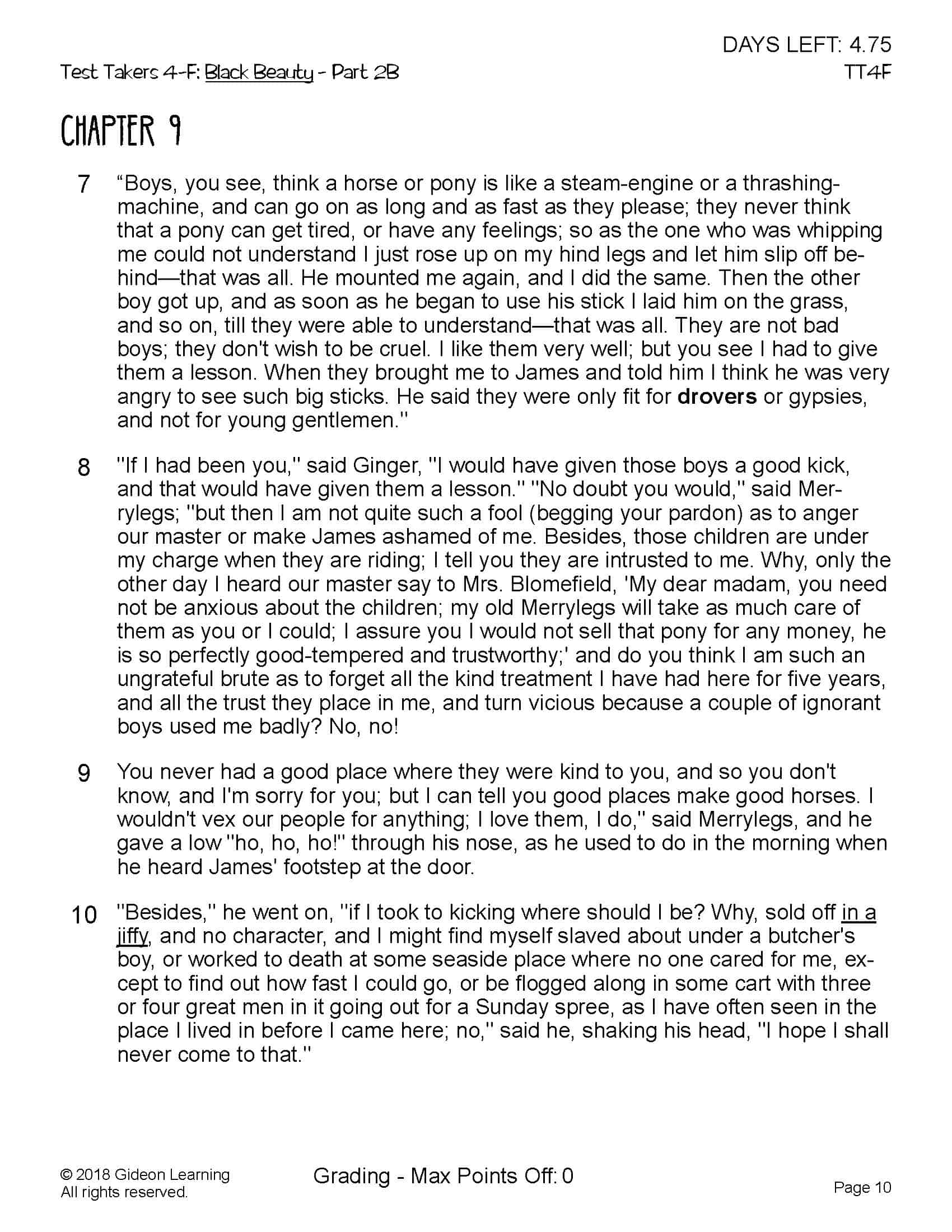

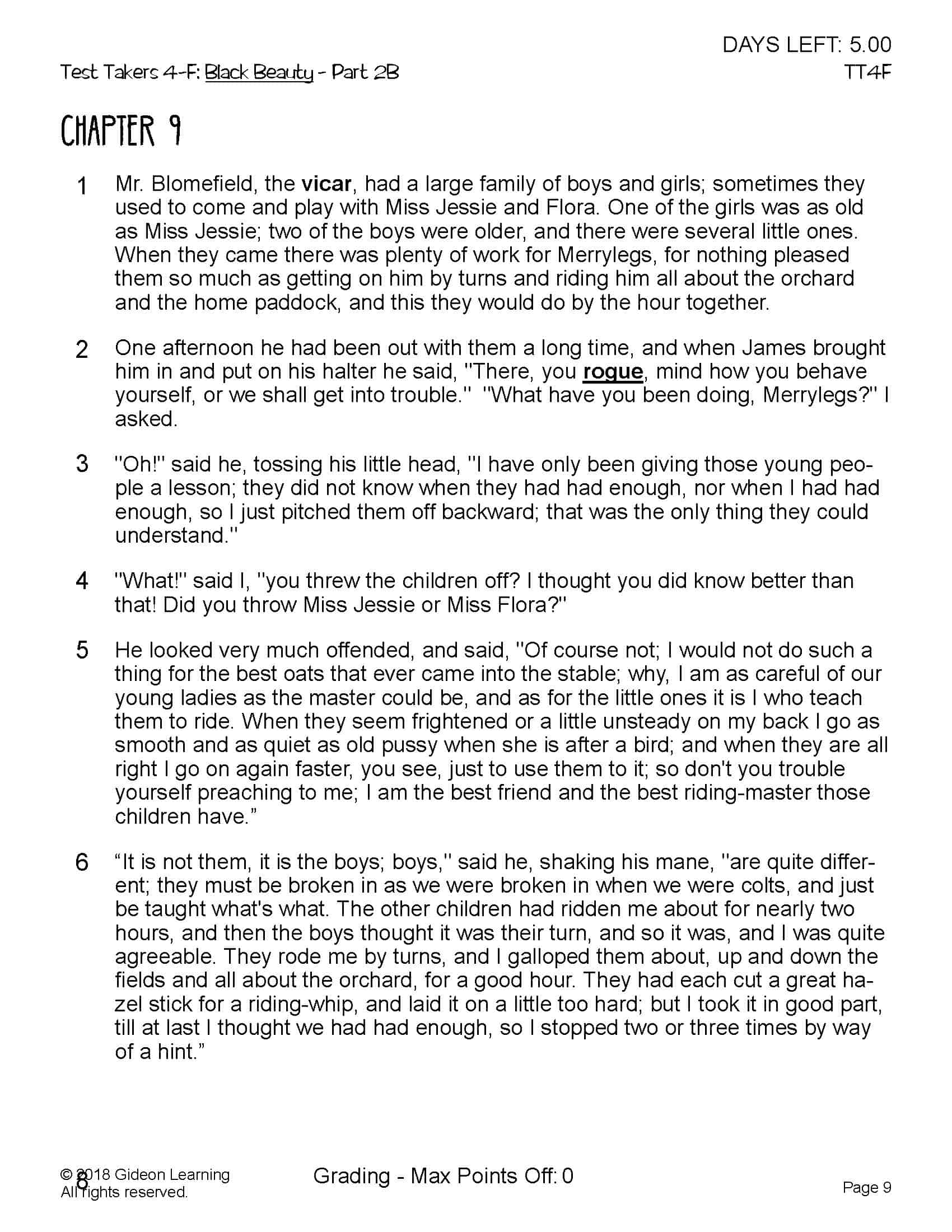

While reading what interests them does keep students reading, parents and teachers ought to push them to continue finding harder materials to digest. At Gideon, we’ve taken classics such as Black Beauty and Swiss Family Robinson and incorporated them with comprehension questions into our program. The passages are longer as many are complete chapters. Some of the vocabulary does require a dictionary as it is outdated, but it creates the habit of looking up unknown words and using context clues. The settings and problems presented in these classics have some great differences to today’s modern world which can make it very interesting to the student; yet at the same time these stories have timeless themes to which they can relate.

Professor emerita of education at the University of Arkansas, Stotsky firmly believes that high school students should be reading challenging fiction to get ready for the reading they’ll do in college. “You wouldn’t find words like ‘malevolent,’ ‘malicious’ or ‘incorrigible’ in science or history materials,” she says, stressing the importance of literature. Stotsky says in the ’60s and ’70s, schools began introducing more accessible books in order to motivate kids to read. That trend has continued, and the result is that kids get stuck at a low level of reading.

“Kids were never pulled out of that particular mode in order to realize that in order to read more difficult works, you really have to work at it a little bit more,” she says. “You’ve got to broaden your vocabulary. You may have to use a dictionary occasionally. You’ve got to do a lot more reading altogether.”

“There’s something wonderful about the language, the thinking, the intelligence of the classics,” says Anita Silvey. She acknowledges that schools and parents may need to work a little harder to get kids to read the classics these days, but that doesn’t mean kids shouldn’t continue to read the popular contemporary novels they love. Both have value: “There’s an emotional, psychological attraction to books for readers. And I think some of, particularly, these dark, dystopic novels that predict a future where in fact the teenager is going to have to find the answers, I think these are very compelling reads for these young people right now.”

Reading leads to reading, says Silvey. It’s when kids stop reading, or never get started in the first place, that there’s no chance of ever getting them hooked on more complex books.

Read the rest of the KERA story

HERE.

Need some help finding the age-appropriate books? Ask your local librarian and check out these LISTS from scholastic.com

Independent Learners, Math

Via JoanneJacobs.com

The author of the blog Math with Bad Drawings is a current math teacher (and former math student) and discusses the feelings and actions of someone who is floundering at math from both his teaching and his own experiences.

As a math teacher, it’s easy to get frustrated with struggling students. They miss class. They procrastinate. When you take away their calculators, they moan like children who’ve lost their teddy bears. (Admittedly, a trauma.)

Even worse is what they don’t do. Ask questions. Take notes. Correct failing quizzes, even when promised that corrections will raise their scores. Don’t they care that they’re failing? Are they trying not to pass?

I noticed the same things while teaching Algebra I and geometry in Austin. I would offer to help during class or in after-school tutoring sessions, but they would simply decline. They would NEVER remember to bring their books to class. And boy, did they show their despair over no calculators on tests and quizzes! I realized then that many of my Algebra I students did not know 6 x 7 and had no clue about negative numbers. These students were able to pass into 9th grade while having failed the previous middle school math courses. While I did as much pre-algebra review as I could, I offered extra drill practice to the students who hadn’t memorized the basic facts yet. Of course, they declined those as well. Six weeks into the year, one failing student simply remarked, “I’ll retake it in summer school.”

The author of the blog had success with math until his senior year topology course at Yale. Then he started to struggle and wasn’t sure how to handle it.

My failure began as most do: gradually, quietly. I took dutiful notes from my classmates’ lectures, but felt only a hazy half-comprehension. While I could parrot back key phrases, I felt a sense of vagueness, a slight disconnect – I knew I was missing things, but didn’t know quite what, and I clung to the idle hope that one good jolt might shake all the pieces into place.

But I didn’t seek out that jolt. In fact, I never asked for help. (Too scared of looking stupid.) Instead, I just let it all slide by, watching without grasping, feeling those flickers of understanding begin to ebb, until I no longer wondered whether I was lost. Now I knew I was lost.

So I did what most students do. I leaned on a friend who understood things better than I did. I bullied my poor girlfriend (also in the class) into explaining the homework problems to me. I never replicated her work outright, but I didn’t really learn it myself, either. I merely absorbed her explanations enough to write them up in my own words, a misty sort of comprehension that soon evaporated in the sun. (It was the Yale equivalent of my high school students’ worst vice, copying homework. If you’re reading this, guys: Don’t do it!)

I had a similar experience with an upper level college math course, Real Analysis, which I have so blocked from my memory I can’t even tell you what it was about. While I didn’t seek out help either (even though I should have!), I made it through due to the curve as it seemed most people were more clueless than me.

The author, finally desperate, did what he should have done all along. Ask for help from the professor!

I was sweating in the elevator up to his office. The worst thing was that I admired him. Most world-class mathematicians view teaching undergraduates as a burdensome act of charity, like ladling soup for unbathed children. He was different: perceptive, hardworking, sincere. And here I was, knocking on his office door, striding in to tell him that I had come up short. An unbathed child asking for soup.

Teachers have such power. He could have crushed me if he wanted.

He didn’t, of course. Once he recognized my infantile state, he spoon-fed me just enough ideas so that I could survive the lecture.

Teachers want their students to TRULY understand the concepts. Almost all are happy to give extra explanations when asked, but they aren’t mind readers. Encourage your children to not be shy.

Sometimes a student starts a question with, “Sorry, but I need help with…” as if they should be ashamed they haven’t mastered it already. I always remind them, “Don’t apologize. This is my job! You are learning, and this is why I’m here.”

I tell my story to illustrate that failure isn’t about a lack of “natural intelligence,” whatever that is. Instead, failure is born from a messy combination of bad circumstances: high anxiety, low motivation, gaps in background knowledge.

Most of all, we fail because, when the moment comes to confront our shortcomings and open ourselves up to teachers and peers, we panic and deploy our defenses instead. For the same reason that I pushed away Topology, struggling students push me away now.

Not understanding Topology doesn’t make me stupid. It makes me bad at Topology.

And I would argue that like many things had the author had more time and asked for more help with topology (or me with Real Analysis) he would have likely gotten a lot better at it. Writing this blog post has me wishing to be able to retake the class, but I imagine that will wait for another day.

Read the rest of this great blog HERE.

Independent Learners, Math, Reading, Young Learners

No one enjoys mistakes, but we all make them. Did you ever think it could be beneficial to admit to them? Kathryn Schulz, the author of Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error writes about the good side to being wrong in this article.

Is there anything at once so routine and so loathed as the revelation that we were mistaken? Like the exam that’s returned to us covered in red ink, being wrong makes us cringe and slouch down in our seats. It makes our hearts sink and our dander rise. Sometimes we hate being wrong because of the consequences. Mistakes can cost us time and money, expose us to danger or inflict harm on others, and erode the trust extended to us by our community. Yet even when we are wrong about completely trivial matters – when we mispronounce a word, mistake our neighbor Emily for our co-worker Anne, make the dinner reservation for Tuesday instead of Thursday – we often respond with embarrassment, irritation, defensiveness, denial and blame. Deep down, it is wrongness itself that we hate.

I remember sneakily throwing away my corrections when I did a program similar to Gideon as a middle schooler. What’s worse than redoing something you already did wrong? It shouldn’t seem overwhelming as you did many more problems in the first time through. You now only have to redo a fraction of them; however, those remaining with the Xs seem like too much. Students occasionally will get upset when they make a lot of mistakes usually when they are working on something new. I always remind them, “We are learning right now! If I make mistakes every day, isn’t ok if you do too?”

As ashamed as we may feel of our mistakes, they are not a byproduct of all that’s worst about being human. On the contrary: They’re a byproduct of all that’s best about us. We don’t get things wrong because we are uninformed and lazy and stupid and evil. We get things wrong because we get things right. The more scientists understand about cognitive functioning, the more it becomes clear that our capacity to err is utterly inextricable from what makes the human brain so swift, adaptable and intelligent.

[Humans] care about what’s probably right, based on whatever we’ve experienced in the past. This guessing strategy is known as inductive reasoning, and it makes us right about vastly more (and more important) things than giraffes. You use inductive reasoning when you hear a strange noise in your house at 3 a.m. and call the cops; when your left arm throbs and you go to the emergency room; when you spot your spouse’s migraine medicine on the table and immediately turn on the coffee, turn off the TV and hustle your tantrumming toddler out of the house.

In situations like these, we don’t hang around trying to compile bulletproof evidence for our beliefs – because we don’t need to. Thanks to inductive reasoning, we are able to form nearly instantaneous beliefs and take action accordingly.

Psychologists and neuroscientists increasingly think that inductive reasoning undergirds virtually all of human cognition – the decisions you make every day, as well as how you learned almost everything you know about the world. To take just the most sweeping examples, you used inductive reasoning to learn language, organize the world into meaningful categories, and grasp the relationship between cause and effect in the physical, biological and psychological realms.

This instinctive feeling and confidence for math is what we aim for at Gideon. This is why we insist students be able to do the addition or multiplication facts within a certain time. If they haven’t memorized it enough to trust what their brain is telling them instantly, then we should do more practice. Similarly, great readers will read a steady, quick pace as they trust their brains are telling them the correct word for the what they see.

But this intelligence comes at a cost: Our entire cognitive operating system is fundamentally, unavoidably fallible. The distinctive thing about inductive reasoning is that it generates conclusions that aren’t necessarily true. They are, instead, probabilistically true – which means they are possibly false. Because we reason inductively, we will sometimes get things wrong.

Instead, it suggests that we should work with rather than against our natural reasoning processes to try to prevent mistakes and mitigate their consequences. This is doable. In fact, it’s been done.

Aviation personnel are encouraged and in some cases even required to report mistakes, because the industry recognizes that a culture of shame doesn’t discourage error. It merely discourages people from acknowledging and learning from their mistakes.

Embracing our fallibility is the only way to build effective backup systems to prevent or mitigate mistakes – whether those systems are as sophisticated as the cockpit of an airplane or (as surgeon and writer Atul Gawande has convincingly argued) as simple as a checklist in the operating room.

We insist all corrections be done at Gideon in both subjects. The students learn what their weaknesses are such as determining if the mistake was careless, improper method, or didn’t understand what to do at all. Then they can create their back-up systems appropriately: slowing down, relearning the method, or rereading the directions or asking help from an instructor. With too many errors, the students are required to redo the booklet. They then can implement their back-up systems and usually make their weaknesses stronger with each repetition. Our thought is that this will also transfer into other subjects and areas of their lives.

Moreover, as it turns out, paying attention to error pays. When the University of Michigan medical system implemented a systemwide policy of admitting medical errors, apologizing to those affected and actively working to explain and compensate for the error, its annual legal fees dropped from $3 million to $1 million. Implementing computerized monitoring systems at every hospital in the country would not only prevent 200,000 adverse drug events each year, but save an estimated billion dollars, according to the RAND Corp.

Once we recognize that we do not err out of laziness, stupidity or evil intent, we can liberate ourselves from the impossible burden of trying to be permanently right. We can take seriously the proposition that we could be in error, without deeming ourselves idiotic or unworthy. We can respond to the mistakes (or putative mistakes) of those around us with empathy and generosity.

Take away the ability of an intelligent, principled, hard-working mind to get it wrong, and you take away the whole thing.

Read the rest of her article here.