Grammar, Independent Learners, Math, Reading, Writing

Yes, Yes, and Yes. I could not agree more!

In this article from TIME, an English teacher describes her negativity towards being required to have her students memorize word roots only to discover how beneficial it was. And that they didn’t hate it! Fancy that!

In an account of her experience in English Journal, she wrote, “asking students to do rote memorization was the antithesis of what I believed in most.” Still, her department head insisted on it, so Kail went forward with the attitude, “I’ll do it, but I won’t like it.” She was sure her students wouldn’t like it, either.

Suzanne Kail’s experience is instructive. As soon as she began teaching her students the Greek and Latin origins of many English terms — that the root sta means “put in place or stand,” for example, and that cess means “to move or withdraw” — they eagerly began identifying familiar words that incorporated the roots, like “statue” and “recess.”

Kail’s students started using these terms in their writing, and many of them told her that their study of word roots helped them answer questions on the SAT and on Ohio’s state graduation exam. (Research

confirms that instruction in word roots allows students to learn new vocabulary and figure out the meaning of words in context more easily.) For her part, Kail reports that she no longer sees rote memorization as “inherently evil.” Although committing the word roots to memory was a necessary first step, she notes, “the key was taking that old-school method and encouraging students to use their knowledge to practice higher-level thinking skills.”

Why memorization has gotten such a bad rap, I’ll never know as we all hear about how Michael Jordan got to legendary status doing thousands of free throws (muscle memorization). Your brain is no different. Want to get better? Practice, practice, practice. You don’t need to analyze the logic behind why 5 x 6 = 30 each and every time. After learning the concept initially, you need to just know it. 30. No finger counting. 30.

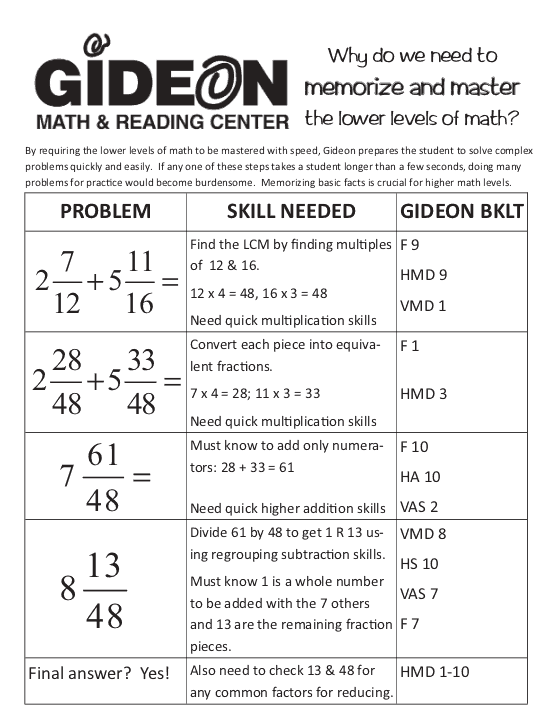

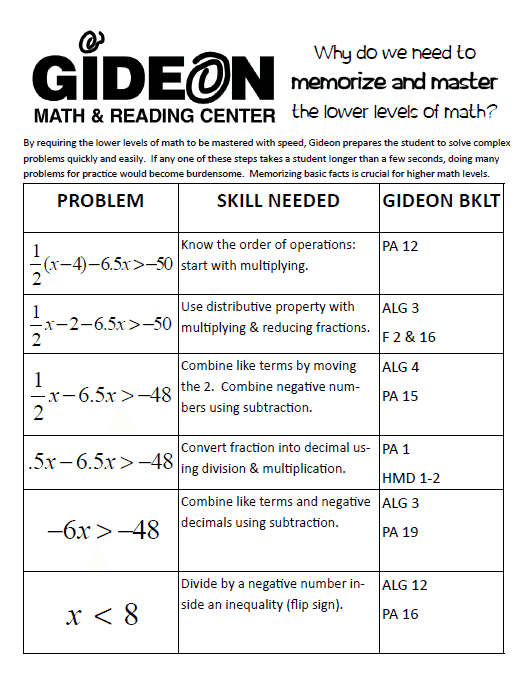

The articles continues with how memorization of math facts is crucial to higher math.

That’s also true of another old-fashioned method: drilling math facts, like the multiplication table. Although many progressive educators decry what they call “drill and kill” (kill students’ love of learning, that is), rapid mental retrieval of basic facts is a prerequisite for doing more complex, and more interesting, kinds of math. The only way to achieve this “automaticity,” so far as anyone has been able to determine, is to practice. And practice. Indeed, many experts who have observed the wide gap between the math scores of American and Chinese students on international tests attribute the Asian students’ advantage to their schools‘ relentless focus on memorizing math facts. Failure to do so can effectively close off the higher realms of mathematics: A study published in the journal Math Cognition found that most errors made by students working on complex math problems were due to a lack of automaticity in basic math facts.

If you want to see an example all the skills needed to solve complex fractions and algebra equations, click HERE to download Gideon’s:

Why Master Lower Levels.

Also for more articles like this, check out

joannejacobs.com who lead me to it initially.

Independent Learners, Math, Young Learners

A new trend is the use of a calculator for EVERYTHING. While we demand mastery at Gideon which requires memorization of basic math facts, many students (from high performing school districts) we see are still counting (or even multiplying!) on their fingers. There is an added problem that with teaching Connected Mathematics which doesn’t see a need to teach long division of larger numbers as it can be done on a calculator and CM sees it as a waste of classroom time.

While doing some education classes at a major Texas university over ten years ago to be able to be certified to teach secondary math in here, I was repeatedly told to incorporate technology into my lessons and show ways it made the lesson more interesting to students. (Is the goal to be interesting or effective?) I’m fairly old school and didn’t see the need for the graphing calculators most of the time, and luckily the school where I student taught (and later taught for 1 year) agreed with me. However, when I taught students fresh out of the local middle school, they were very upset with me when I did not allow calculators on quizzes or tests. Many could not tell me 6 x 8 in Algebra I as ninth graders.

When Longfellow Middle School in Falls Church, Va., recently renovated its classrooms, Vern Williams, who might be the best math teacher in the country, had to fight to keep his blackboard. The school was putting in new “interactive whiteboards” in every room, part of a broader effort to increase the use of technology in education. That might sound like a welcome change. But this effort, part of a nationwide trend, is undermining American education, particularly in mathematics and the sciences. It is beginning to do to our educational system what the transformation to industrial agriculture has done to our food system over the past half century: efficiently produce a deluge of cheap, empty calories.

I went to see Williams because he was famous when I was in middle school 20 years ago, at a different school in the same county. Longfellow’s teams have been state champions for 24 of the last 29 years in MathCounts, a competition for middle schoolers. Williams was the only actual teacher on a 17-member National Mathematics Advisory Panel that reported to President Bush in 2008.

Williams doesn’t just prefer his old chalkboard to the high-tech version. His kids learn from textbooks that are decades old—not because they can’t afford new ones, but because Williams and a handful of his like-minded colleagues know the old ones are better. The school’s parent-teacher association buys them from used bookstores because the county won’t pay for them (despite the plentiful money for technology). His preferred algebra book, he says, is “in-your-face algebra. They give amazing outstanding examples. They teach the lessons.”

Technology is designed to make our lives easier, but there are some skills that should be learned anyway. Let’s say fractions is difficult for you, and the calculator will give you the answer easily. Should you never bother to learn how to add fractions? This is similar to saying that since I don’t like to cook and there are plenty of restaurants, I shouldn’t bother to learn how to cook. There may be situations you need to be prepared for – such taking the GMAT where a calculator isn’t allowed in the quantitative section or in my cooking case, needing to save money by eating at home. Konstantin continues:

Math and science can be hard to learn—and that’s OK. The proper job of a teacher is not to make it easy, but to guide students through the difficulty by getting them to practice and persevere. “Some of the best basketball players on Earth will stand at that foul line and shoot foul shots for hours and be bored out of their minds,” says Williams. Math students, too, need to practice foul shots: adding fractions, factoring polynomials. And whether or not the students are bright, “once they buy into the idea that hard work leads to cool results,” Williams says, you can work with them.

Click here to read the rest of this article.

Independent Learners, Math

Maybe I’m a math nerd (ok, I am), but asking whether Algebra I is necessary seems crazy. Whenever I hear the argument we should not teach higher math to all students as most won’t use it, I always think, but how do you know which ones? Would you want your child pushed into a non-math tracking due to one bad test score in 6th grade? What if she decided to be an engineer later, only to realize she was dreadfully behind in needed math skills? I wouldn’t want to limit any student’s career choices as early as ninth grade.

It has been argued that since we are failing as a country to teach Algebra I to most students we should simply stop. What kind of attitude is this? This isn’t a failing business that should shut down; this is many students’ future career paths at stake. If we want the highly technical jobs going to American citizens, we better be teaching them math. And trying to do it better, rather than lying down giving up! How many teenage students would gladly not bother with Algebra I if not required due to immaturity, only to regret it upon discovering that their college majors choices are limited without major remediation?

Several articles responded to an initial argument for it be a non-requirement. Daniel Willingham at the Washingtonpost.com wrote:

When I first saw yesterday’s New York Times op-ed, I mistook it for a joke.

Unfortunately, the author, Andrew Hacker, poses the question in earnest, and draws the conclusion that algebra should not be required of all students.

His arguments:

* A lot of students find math really hard, and that prompts them to give up on school altogether. Think of what these otherwise terrific students might have achieved if math hadn’t chased them away from school.

* The math that’s taught in school doesn’t relate well to the mathematical reasoning people need outside of school.

His proposed solution is the teaching of quantitative skills that students can use, rather than a bunch of abstract formulas, and a better understanding of “where numbers actually come from and what they actually convey,” e.g., how the consumer price index is calculated.

For most careers, Hacker believes that specialized training in the math necessary for that particular job will do the trick.

What’s wrong with this vision?

The inability to cope with math is not the main reason that students drop out of high school. Yes, a low grade in math predicts dropping out, but no more so than a low grade in English. Furthermore, behavioral factors like motivation, self-regulation, social control (Casillas, Robbins, Allen & Kuo, 2012), as well as a feeling of connectedness and engagement at school (Archambault et al, 2009) are as important as GPA to dropout. So it’s misleading to depict math as the chief villain in America’s high dropout rate.

What of the other argument, that formal math mostly doesn’t apply outside of the classroom anyway?

The difficulty students have in applying math to everyday problems they encounter is not particular to math. Transfer is hard. New learning tends to cling to the examples used to explain the concept. That’s as true of literary forms, scientific method, and techniques of historical analysis as it is of mathematical formulas.

…

Hacker overlooks the need for practice, even for the everyday math he wants students to know. One of the important side benefits of higher math is that it makes you proficient at the other math that you had learned earlier, because those topics are embedded in the new stuff. (e.g., Bahrick & Hall, 1991). So I think there are excellent reasons to doubt that Hacker’s solution to the transfer problem will work out as he expects.

What of the contention that math doesn’t do most people much good anyway?

Economic data directly contradict that suggestion. Economists have shown that cognitive skills — especially math and science — are robust predictors of individual income, of a country’s economic growth, and of the distribution of income within a country (e.g. Hanushek & Kimko, 2000; Hanushek & Woessmann, 2008).

…

There are not many people who are satisfied with the mathematical competence of the average US student. We need to do better. Promising ideas include devoting more time to mathematics in early grades, more exposure to premathematical concepts in preschool, and perhaps specialized math instructors beginning in earlier grades.

Hacker’s suggestions sound like surrender.

AMEN!! Click here to read the full article.

Also from joannejacobs.com:

Kids who can’t understand math usually can’t read well either, writes RiShawn Biddle on Dropout Nation. “The very skills involved in reading (including understanding abstract concepts) are also involved in algebra and other complex mathematics.”

Independent Learners, Math, Young Learners

From Joannejacobs.com

Many teachers say they’re not well-prepared to teach math, according to an excerpt from a new book, Inequality for All, by William H. Schmidt and Curtis C. McKnight.

In first through third grade, teachers feel prepared to teach only grade-level math topics, a survey of Michigan and Ohio teachers found. In some districts, only half said they were ready for grade-level math. (My first husband said his sister became a second-grade teacher because she couldn’t do third-grade math. This, apparently, is not a joke.)

Upper elementary teachers were more confident, though only one fourth of teachers in one district said they were well prepared to teach decimals.

Only 50 to 60 percent of middle school teachers felt well prepared to teach math topics in Michigan and Ohio standards. Both states plan to introduce algebra topics in eighth grade, but only half the teachers are ready.

Click here to read more. While it is a bit better for high school teachers, it still makes you wonder what kind of foundation is being laid?

This idea is also brought to discussion in the book, Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics by Liping Ma where she discusses the major difference between Chinese and American elementary school teachers’ understanding of basic math concepts (something such as multi-digit multiplication). While many Chinese teachers do not have as much schooling as their American counterparts (only 11 to 12 yrs. vs. 16 to 18 yrs.), the Chinese teachers understanding of the CONCEPTS was far superior as most American teachers in the study (even those with 10+ years experience) were only comfortable with the procedure. Many could not explain why a zero is put on the second row with multiplying something such as 42 x 63, only knowing it is what has always been done.

Independent Learners, Math

From joannejacobs.com & usatoday.com

“Our kids hate math” because they’re pushed to learn higher math before they’ve mastered the basics, writes Patrick Welsh, who teaches at T.C. Williams High in Virginia, in USA Today.

The experience of T.C. Williams teacher Gary Thomas, a West Point graduate who retired from the Army Corps of Engineers as a colonel, is emblematic of the problem. This year, Thomas had many students placed in his Algebra II class who slid by with D’s in Algebra I, failed the state’s Algebra I exam and were clueless when it came to the most basic pre-requisites for his course. “They get overwhelmed. Eventually they give up,” Thomas says.

While teaching Algebra I for 9th graders ten years ago in Austin, TX, I found many students did not know basic multiplication facts and wanted to use a calculator for everything (which I denied). Negative numbers and fractions were topics where even more students had no mastery and made a lot of mistakes. Students who had failed middle school math were still placed into my class. It’s very difficult to learn algebra without this background knowledge. It’s like trying to read a sentence without being able to sound out some of the words! You get stuck and can’t move on.

The article continues, “It is time to ensure that all kids absorb the fundamentals of math — computation, fractions, percentages and decimals — first before moving on to the next level,” Welsh concludes.

At Gideon, we have seen that almost any child can excel at math — given the time to master it. The time will vary from student to student. Some students only need a couple of days to master adding fives, while others will struggle for several weeks. BUT! If we persevere with the practice, the student will get it! (And when you ‘get’ something, you don’t tend to ‘hate’ it. I know MANY kids that enjoy math very much.)

If you move on too soon (before memorization), the student will continue to need crutches (such as: finger counting or dot patterns) to calculate addition facts. The larger issue of not getting a solid foundation with the basics is that the struggle with math snowballs each year into something bigger. Think of each skill that is not mastered creating a new layer of snow creating more speed and weight to pull the student down.

This leads to trouble with long division (skills needed: subtraction, multiplication, and division) and fractions (skills needed: addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and others!), and usually the big hit comes in Algebra I with the culmination of so many unmastered basic skills required for a single equation to be solved. The student’s work pace slows to a crawl. It’s no wonder students who do not get that solid foundation would find basic Algebra and beyond a miserable experience. However, if you will go to the root of the problem, it can be solved. No matter what the age or grade! Just expect to put in the time and effort as with anything that you want to improve.

Joanne Jacobs adds, “A frightening number of students never learn math fundamentals. It’s the single greatest barrier to success in community colleges, which attract the un-stellar students. Students who’ve passed high school math classes — including a class called algebra — don’t understand fractions, percentages or decimals and can’t multiply 8 x 4 without a calculator.”

Read the rest of Joanne Jacobs’s comments here or the rest of the original usatoday.com column here.

Part of the problem may be the move away from algorithms to teach more numerical reasoning. Read more here.